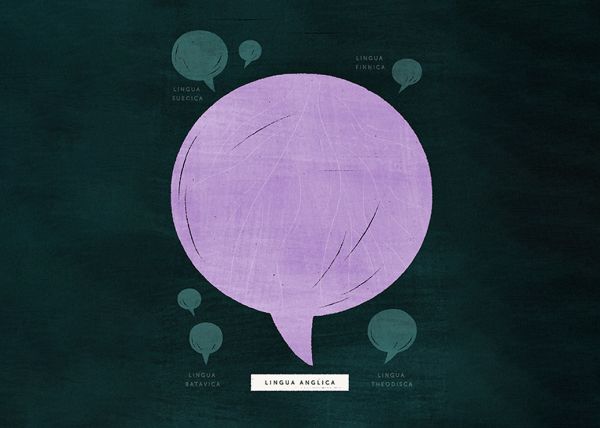

A significant part of master’s degree programmes at the Finnish universities are in English, and nearly 40 percent of master’s theses are also written in English. If this trend continues, English will soon be the language of Finnish science, fears a Ministry-appointed evaluator.

When Ian Hardy, currently the Professor of Agricultural Entomology at the University of Helsinki, headed to the Netherlands after completing his PhD about two decades ago, he decided to learn the local language.

While he would have managed with English in the scientific community, Hardy tried to keep up with his department’s break room conversations and told the others not to switch to English.

The work paid off. His five-year stint in the Netherlands left him with a grasp of the language, which he still uses when meeting Dutch colleagues at conferences.

However, he has recently noticed something odd.

“When I meet younger Dutch entomologists, they can’t always talk about insects in Dutch. Sometimes, I know the Dutch terms better than they do. That is quite strange”, Hardy wonders.

Heading the way of the Dutch

Hardy’s observation comes as no surprise to linguist Janne Saarikivi. The Professor of Sami Languages at the University of Tromsø in Norway and linguistic multitasker informs us that the universities in the Netherlands already conduct more of their operations in English than in Dutch. 70 percent of master’s degree programmes in these universities are in English, and so are 60 percent of bachelor’s degree programmes. Master’s degree programmes in Dutch are available mainly in fields whose degrees relate directly to the needs of working life, such as education, health care, and law.

“This means it’s no longer possible to get the highest-level education in many fields in the country’s national language, which is also the native language of most students”, Saarikivi describes.

”It’s no longer possible to get the highest-level education in many fields in the country’s national language, which is also the native language of most students.”

Janne Saarikivi, linguist

Saarikivi sees the situation in the Netherlands as an extreme example from a European standpoint, but hardly unique.

“We are heading the same way in Finland as well.”

The law and the reality at odds

Saarikivi’s view is based on the report on university language choices he has been working on with MA Jani Koskinen. The previous government’s Minister of Science and Culture Petri Honkonen ordered the report, entitled Monikielistä sivistystä vai englanninkielisiä ratkaisuja? Selvitys yliopistojen kielivalinnoista. (en. Multilingual education or English language solutions? A report on university language choices.)

According to the report, English is taking over the Finnish universities at a rapid rate. One example of this is the language of theses.

In 2011, eight percent of approved bachelor’s theses were written in English. Ten years later, the figure had already jumped to 30 percent. 30 percent of master’s theses were written in English in 2011, but a decade later this had increased to 38 percent.

Based on doctoral dissertations, we can already consider English the language of science, as a whopping 86 percent of dissertations reviewed across all Finnish universities were written in English.

Based on doctoral dissertations, we can already consider English the language of science.

“These are tough figures for the universities, which supposed to operate in either Finnish or Swedish according to the University Act”, Saarikivi notes.

Legally, other languages may be used at the universities as required.

There is no end in sight for the trend. The Ministry of Education and Culture has announced the goal of tripling the number of international students by 2030.

“Under the current model, this would mean a massive increase in English student places. Finnish would be left behind even more”, Saarikivi predicts.

He suspects the situation might even be against the law.

“In 2010, the University of Helsinki was issued a decision by the Parliamentary Ombudsman, stating that education must be provided in the legal degree languages. In 2013, the Chancellor of Justice and the Parliamentary Ombudsman issued the same decision regarding the Aalto University’s Engineering Studies languages. Yet, the situation has only worsened.”

It all goes back to Bologna

What has caused this situation, then? According to Saarikivi, it all stems from the pan-European Bologna Process, in which a common university system was created for all of Europe. The idea was to allow students to move between countries based on their interests.

The system’s idea of all these universities becoming more international was certainly pleasant. However, when creating the system, not enough thought was put into what this international approach would mean from a language politics standpoint.

Since we assume everyone knows English, in practice this internationalisation has led to university education becoming increasingly English throughout the continent. Especially in the master’s degree stage, a large number of lessons are in English now.

This especially presents a problem in Finland because we consider a master’s degree a basic diploma required on the labour market.

Saarikivi wonders who this situation benefits.

“As part of the report, we conducted both focus group interviews and a survey for students. A clear majority of the respondents wanted more teaching in the national languages and less in English.”

The University of Helsinki does not agree

Not everyone sees the situation quite so grimly. On the contrary, University of Helsinki Vice-Rector Hanna Snellman, responsible for international affairs at the university, believes the University of Helsinki is defending the status of the national languages.

“Aside from specifically agreed exceptions, the student is always allowed to hand in their coursework in the national language”, Snellman says.

“While the majority of the university’s master’s degree programmes are international, that does not mean they are exclusively in English. Of course, English is used plenty, but so are the national languages. The big role of the national languages has raised some eyebrows abroad, but we have decided to hold on to it.”

Snellman also calls the report’s focus group interviews into question.

“I have conducted interview surveys myself and know that the most eager respondents are those who think things are going wrong. I would not be too eager to draw conclusions about how much the interview results represent the student body or university personnel as a whole.”

“I would say the report reflects its author. Someone else might have focused on different things.”

Oulu invests in teaching Finnish

Eva Raudasoja, Director of the University of Oulu’s Extension School, says the university has consciously increased the use of the English language.

“We want to ensure the inclusion of international student as well. Our goal is to produce information in both Finnish and English to allow everyone to participate.”

At the same time, the university invests in teaching Finnish.

“Most of our international programmes allow students to study Finnish either as part of the degree or as an option. At the university, you manage well in English but the working environment around here largely operates in Finnish. It is hard to integrate without knowing the language”, says Katja Nieminen, the university’s Head of International Affairs.

“At the university, you manage well in English but the working environment around here largely operates in Finnish. It is hard to integrate without knowing the language”

Katja Nieminen, Head of International Affairs, University of Oulu

In 2021, 30 percent of master’s theses and 9 percent of bachelor’s theses at the University of Oulu were written in English. Even though the number of master’s theses in English has doubled in the last decade, Raudasoja and Nieminen are not concerned about the status of Finnish at the university.

“Some other universities may choose a policy with English in a more central role, but our guiding principle is still multilingualism. English is part of it, but I do not see it threatening the status of Finnish.”

Aalto on its own

Out of all the universities in Finland, the Aalto University is most prominently highlighted in the report. At Aalto, English plays a larger role than anywhere else. Nearly half of the university’s bachelor’s theses – 45 percent – are written in English. For MA theses and diploma theses, the number is 84 percent.

English also dominates the training programmes. The evaluators found 94 training programmes exclusively in English at the university. Three were exclusively in Finnish. In early May, Deputy Chancellor of Justice Mikko Puumalainen issued a complaint decision stating that linguistic rights are realised only superficially at the university and that the situation is a violation of the University Act.

English also dominates the training programmes.

Aalto University Vice President for Education Petri Suomala asserts that Aalto still remains a Finnish and Swedish-language university.

“The general rule is still that the student may hand in their theses and exam answers in the national languages, although that is not always possible on all English-language courses.”

And can you study entirely in English at Aalto without being exposed to Finnish at all?

“That is not our goal here. Everyone is offered the opportunity to learn Finnish as well. But I expect it would be possible, should someone wish to do it.”

In his report, Saarikivi presents a threat scenario in which the increased use of English at the universities marginalises Finnish into a “kitchen language”, which could eventually even threaten Finland as a nation. Suomala finds the idea an exaggeration.

“Our researchers talk about research daily in Finnish media, also in Finnish. I do not like to think of Finnish as some kind of isolated island – we need international connections to the global scientific community, and English is the language of that cooperation. If you want your research to be read, you should use English.”

What if we take upper secondary school students instead?

Saarikivi, on the other hand, is serious about his concerns about Finnish drifting to the margins. He believes the internationalisation development has taken the wrong approach. It would be essential to get incoming students to learn Finnish first and only then start teaching them.

“One way could be to start international branches in places like China or India. There, the students would study Finnish along with their major subjects. Later in their studies, they would come to Finland to study in Finnish.

His second idea sounds even wilder – students could come to Finland right after primary school to start upper secondary school.

“In various regions, we have plenty of upper secondary schools but not enough students. If we took in international students as teenagers, they would have more time to learn the language.”

Is learning the language that crucial, then?

“If we look at what keeps international students in Finland, the main factors are a Finnish spouse and speaking Finnish. We can’t ensure a Finnish partner for everyone, but we can ensure language skills if we want to.”

Norway’s strict demand

Well, how about researchers? Saarikivi uses Norway as an example. International staff at the Norwegian universities are expected to learn the language in three years to be able to teach in Norwegian. They may also use their working hours for studying.

Saarikivi finds this model excellent, but Snellman from the University of Helsinki and Suomala from Aalto are not convinced.

“The Norwegian universities do not like politically prescribed model. It’s also a dead letter. The universities would not boot out their researchers even if they did not learn Norwegian”, says Snellman.

Suomala from Aalto reckons such a decision would reduce recruitment opportunities.

And what says Hardy, the Professor of Agricultural Entomology, who moved to Finland in 2021. Would he have come to Finland if learning Finnish was required?

“That does sound like quite a harsh demand. I have about ten years left in my career, and spending several years learning the language would be quite a lot.”

Of course, he is studying Finnish alongside his work.

“One hour a week might not be enough for me to promise to lecture in Finnish someday.”

Students hope for freedom of choice

Language as required

Aalto University Business and IT student Kim Jokinen sees no issue with the languages used at campus.

Aalto University Business and IT student Kim Jokinen sees no issue with the languages used at campus.

“I already studied in English throughout upper secondary school and applied for an English BA programme at Aalto, so I knew what to expect.”

Fluent in Finnish, Swedish and English, Jokinen has used all three languages in his studies. He says his exam answers are always in the same language as the questions.

Jokinen does not expect the English terminology to be an issue in working life.

“English is becoming more and more common in working life as well. Many international businesses already use it as their corporate language.”

False advertising for Swedish

Calling the Aalto University’s engineering studies bilingual is starting to become false advertising, says Aalto University Energy Technology MA student Wilma Branders.

Calling the Aalto University’s engineering studies bilingual is starting to become false advertising, says Aalto University Energy Technology MA student Wilma Branders.

“When a Swedish-speaking physics professor switched jobs, a new one was not hired. That means even the basic physics studies are not available in Swedish. That is pretty incredible when the university advertises Swedish as well”, Branders marvels.

In the BA stage of her studies, Branders used the right to answer in Swedish in exams. Occasionally, the questions were so poorly translated that she had to look at the Finnish version to see what was actually asked.

Currently, she is continuing her studies in an English MA programme. She does not consider this a problem.

“I am mostly bothered by the fact they promise something that is not true. I am bilingual so I manage fine, but the lack of Swedish can be a real challenge to others”

English is important for a Persian

Aalto University Contemporary Design MA student Pegah Shamloo ended up at Aalto from Tehran due to her interest in Alvar Aalto’s legacy and desire to study in Europe. The main criteria for her choice were the offer of free studies and an English-language programme.

Aalto University Contemporary Design MA student Pegah Shamloo ended up at Aalto from Tehran due to her interest in Alvar Aalto’s legacy and desire to study in Europe. The main criteria for her choice were the offer of free studies and an English-language programme.

“I was also offered a place in Milan. If I could not study in English at Aalto, I would have gone there.”

Shamloo says she is also studying some Finnish, but everyday university life is manageable in English as well.

“Of course, a lot of Finnish is spoken around me, but I think that is completely natural when most students are Finnish. Everything that’s necessary is arranged in English as well.”

She is not worried about the job market either.

“I know Persians who live here. Many of them work in expert positions where English is the working language.”

Shamloo finds the idea of Finnish language proficiency being demanded from international students nationalistic in the wrong way. Finnish is a very unique language, and even English does not help much with learning it.

“By offering free studies to foreign students, the university and Finland can choose who they want. Many of them will stay in Finland. If learning Finnish was made a requirement for admission, the number of people wanting to come here would definitely decrease.”

Text: Juha Merimaa

Illustrations: Outi Kainiemi

Photos: Wilma Branders, Kim Jokinen, Pegah Shamloo

English translation: Marko Saajanaho